Sibylle Omlin

Fields of Painting

On the Pictures and Picture Objectsof Bignia Corradini to Today

Color is the space where our brain

and the universe meet.

Paul Cézanne

A cold January day in Berlin. The bus drives over the River Spree, stops after a long curve, and I alight. On the street, behind a wall stands an elongated clinker brick structure that forms a courtyard situation with several buildings. I walk through a gate and stand in the courtyard, which is surrounded by several buildings. The view towards the south is open. In the west, in entrance J, is where Bignia Corradini’s studio is located. On the fourth oor, I go down a hallway and knock on the door. Bignia Corradini opens. An energetic lady, not very tall, with a blond, short haircut and glasses. The studio is a bright room, pictures stand stacked against a white wall, the windows look out into the courtyard. A small table is laid with fruits in various colours, nuts, and sweets. Bignia makes tea. We first sit down and talk for a while about life, about Berlin. About this and that.

Bignia Corradini has lived in Berlin since 1972, has thus witnessed the history of the city, the Wall, the intense 1980s in punk, politics, and art, and the opening up of the city after the fall oft he Wall; Berlin, which would once again become the capital and thus a real international centre. Like so many Swiss artists, she found a centre for her life and work here. Studios, colleagues, discourse, museums, exchange. Whenever big historical upheavals and events have taken place in the city, as Bignia Corradini tells me, she has lost her studio. After the fall of the Wall in 1989, she experienced the enormous increase in rents. A real-estate conglomerate recently bought the Kreuzberger Gewerbehof (industrial complex): a restructuring took place on the big, old factory oor at Erkelenzdamm, where Bignia Corradini had worked for twenty years. She has now been based in Charlottenburg for four years. It is no coincidence that she still found something in the old West of Berlin, she says. There’s a building custodian and ... heating! We sit at this small, round table, which looks like a colourful tondo— around us, her art. A diamond-shaped, reddish-yellow picture hangs on a small wall; next to us, rectangular canvases stand at the ready in a block. Bignia gets up, begins sorting through the pictures, and hangs the rst one on the large empty wall.

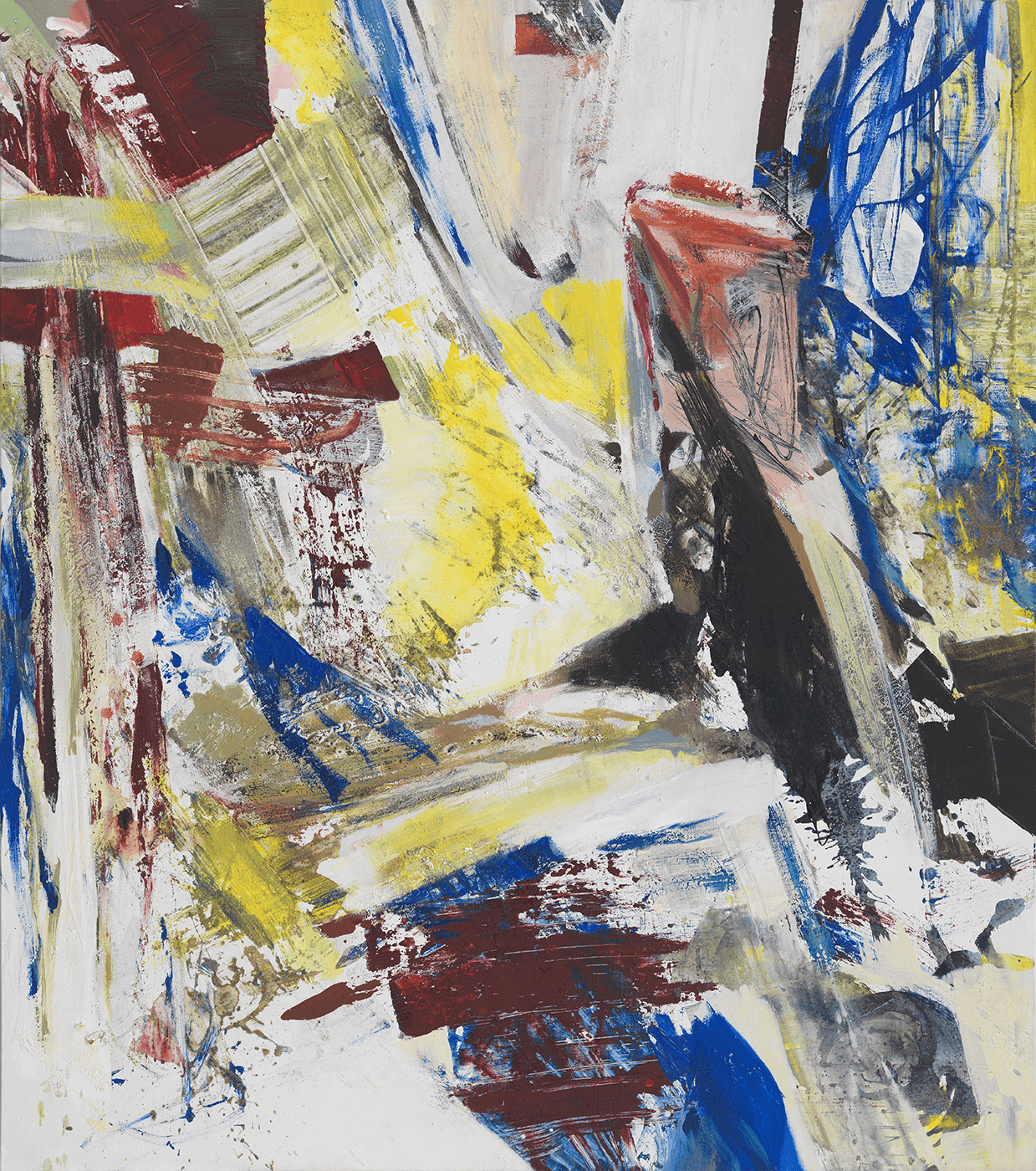

Tacet, 2002, acrylic on canvas, 130 x 180 cm, bright yellow in the right portion of the picture

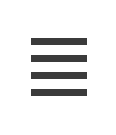

AOIN, 2012, acrylic on canvas in a mirror box with four mirrors, wooden frame, 97 x 97 cm

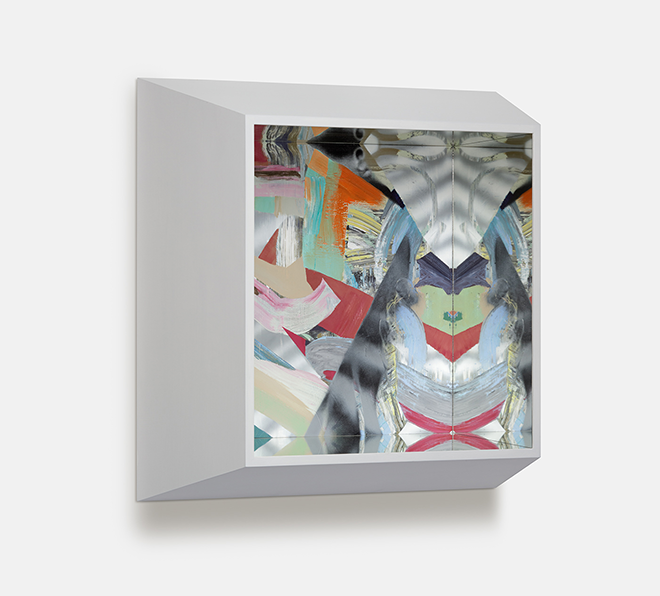

Durchzug, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 170 x 150 cm, blue once again, a loop

Lichtung, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm,

Transfer, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 170 x 150 cm, a striking red spot spills out over the white like a cascade.¹

The colours cover the formats in bands and fields. The picture surfaces often consist of fields densely layered over one another, which always still allow one corner, one band, to peek out from underneath. There are hardly any sparse areas, let alone a view of the naked canvas; the final layer of paint application is closed in a complex way. The paints are applied and spread out with a wide brush, the colour rhythms closely positioned and worked densely into one another.

Painting is slow. Bignia Corradini’s art is created simultaneously in series of several pictures. In the years 2001 to 2005, she also created many picture objects, beautifully processed forms of wood that extend the colour over the various edges. The painted spheres often stand on mirror surfaces. Mirror boxes with coloured walls demand examination. In the years 2008 to 2009, tondi and rhombuses dominated in her work. She tells me that experimenting with the hanging in a big studio space is still important today and takes her further. Simulating exhibition situations. During the visit to her studio, I suddenly realize that I have not yet seen any of Bignia’s exhibitions.

‘Going out into space with my painting has been a need of mine since the 1990s’, says Bignia Corradini and takes a sip of tea. The white wall therefore becomes the carrier, just as the canvas otherwise. The spaces have not only been classic exhibition spaces, but also empty office buildings, marble-cased private banking spaces, and former factory halls. Over three decades, Bignia Corradini has therefore obtained a distinctive ability to place and position her pictures in space, to experiment with them. Painted wooden objects in polygonal geometric forms next to right-angled formats. Small and large. Tondi and rhombuses to painted spheres, spheres next to columns and in front of mirrors.

Hanging and positioning works in space are part of painting, the artist finds. With her picture objects and paintings, she composes groups in corner situations of the exhibition space, positions picture objects on the surface, has tondi hang freely from the ceiling. ‘At the latest since 2003, in the exhibition in Arbon, where I presented pictures on canvas along with 240 painted picture objects of wood, painterly and real space entered into dialogue with one another. My gallerist, Adrian Bleisch, temporarily rented six factory spaces at Hamel AG. There, I was then able to present the picture objects based on the space. It was not a real exhibition space, so time didn’t play a role. The Swiss jazz pianist Irène Schweizer also gave a solo concert in those spaces.’

Sitting, looking, and telling stories in the studio is something I have always liked a lot. Pulling out pictures and then letting them stand in the space in wild combinations. The spines of the artist’s books and catalogues on shelves. The postcards with pictures by other artists that are always lying around somewhere. They generally hang around in the studio for many years, well thumbed, with spots of colour on the blank sides. In Bignia Corradini’s studio, there are cards from Italy, the Annunciation of Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi (1333) for the altar of St. Ansanus in the Cathedral of Siena and the Annunciation of Fra Angelico (ca. 1442) in the Convent of San Marco in Florence. Apart from them, a card of the Apocalypse Rose from the Sainte- Chapelle in Paris. Many architectural elements regulate painting: columns, ower vases, window frames.

In Bignia Corradini’s studio, I try for a long time to see and understand what interests her. I see grey, green, and blue fields and lines of colour applied to the picture format with a wide brush and great energy. The colours generally contrast with each other, but not in complementary combinations. Transitions are important. A wide field near the centre often determines the pictorial narrative. A red as in Transfer of 2015. Colour is important. ‘In painting, colour represents the only truth’, as Theo von Doesburg once wrote ²

The strokes of colour at the end of the application are not completely filled in, but frequently frayed. The brush leaves most of the paint it carries behind in small spots and points. It is therefore always possible to see lower layers of the picture in a complex application of paint in various layers. I imagine that the colours of the lower layers conflict with one another, just as do those on the surface. But, Bignia Corradini’s pictures rarely concern ground and surface. One instead has the feeling that every field of colour has to find its own place, even if it overlays or challenges another. Collisions, long edges in irregular, parallel existence run through the formats and are a defining element in her painting. A roof covered with freely moulded bricks. The diagonal—always an important element in nearly all her pictures. But also fine, shimmering transitions from one colour to the next. Like metal. Like shimmering on a computer screen. Hard, artificial. Some of the pictures make me think of indecipherable cartographies, of the metropolis, seen from an airplane, the edge of a wing in the middle of the view.

‘For me, colour is “field” in its appearance, not linear’, Bignia Corradini says. ‘My pictures are constructed; the individual pictorial elements are positioned, opposed, composed. There are contrasts and connections. The transitions interest me the most. In this sense, they are constructed, a construct.’ Bignia Corradini is very clear and present in her thinking about what she does.

Linear thinking does not interest her in any way. The collective, parallel existence, everything at once ... These are words she repeats again and again. The great complexity in the transitions between the individual moments, all of this meant to work together, ‘... and exactness must prevail in it!’ Bignia Corradini places great demands on herself and her painting, and she also wants to bring her own temperament into this work. The titles of her pictures speak of this.

Abstraction, as we art historians read in the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Richard Paul Lohse, or Max Bill, is a conflict between intuition and calculation, between spontaneous energy and mathematical precision. ‘It is ultimately about’, writes Ettore Sottsass Jr., ‘giving an unwieldy and viscous material lightness, giving it form and meaning, seizing it from below and whirling it into the air, giving the mass a startling and unforeseen movement. This is the real problem, and the solution to it is what constitutes art.’³ Today, one no longer sees pictures the way Bignia Corradini paints them very often. Per Kirkeby’s abstractions always showed a complex interlayering of dark and light fields of colour. In the 1980s, one could see in Wilhelm de Kooning’s painting how he pushed his female figures on the picture format ever further into the paint. Figure and ground could barely be recognized as separate from one another.

Since the mid-1980s, Bignia Corradini has occupied herself with colour associations. A great constancy in the formal can be observed in this part of her oeuvre. What is concerned is an eventful positioning of paint, always acrylic, hence fully covering, thrusting into one another, and always on the search for contrast in the smallest and most confined space. The pictorial elements are painted freely in a gestural manner, do not adhere to any strict geometry, but are clearly derived from it. The pictures frequently show rectangular fields worked into one another that are accompanied, framed, or separated by wide, diagonally positioned bands—length- and crosswise. The application of paint, the texture of painting—transparent glazes and a thick, viscous paint mass—also proves to be a constant over a longer period. In the 1990s, paint was now and then dripped, smudged, applied with the hand. What has changed is the palette. The colours are always central: in the 1980s, the primary colours and green were often embedded in black and white. The pictures of the 1990s, in contrast, frequently show a mixture of brown, ochre, yellow, and green. In the 2000s, more blue was added. The colours become more broken, and new combinations interest her: pink, salmon, turquoise, but also off-white or a metallically shimmering grey.

In the new millennium, painting in contemporary art has shown itself to be spirited and free. Anything is possible. Abstraction has become cooler, more metallic in colour; the colours of monitor screens are incorporated in the painting; the guration and the surreal picture content celebrated new importance round 2003 and 2004 with the young painters from Leipzig. Abstraction has also once again increasingly come to enthuse younger artists. Cecily Brown in England, and Katharina Grosse in Germany. Gerhard Richter is still the figure who surveys everything.

Bignia Corradini sees all of this. She remains true to a form of non-representational painting based on very old layers of this artistic form. Whereby the term, as already at the beginnings of abstract painting in the early twentieth century, gives rise to problems and conflict. When looking at abstract pictures, one is actually again and again tempted to make comparisons with other fields, to incorporate thoughts from philosophy, mathematics, and science.

We peel oranges and come to talk about Didi-Huberman’s Phasmes,⁴ a book that fascinates both of us. ‘The Phasmen!’, Bignia Corradini shouts it loudly into the room, ‘what fascinated me in his text is the moment of their “appearance”. They are there and not there, and you don’t see them; when you look for a long time, you then see them again. Something is shown and concealed at the same time.’

This appearing and simultaneous not-being-there is also a recurring moment in Bignia Corradini’s pictures. It is not easy to capture, when looking, when describing. The diagonal. It again and again provides stability in this constant back and forth. It divides into two halves, but also links in the case of crosswise and lengthwise.

‘Don’t you think as well that colour, when it’s used in painting, always has something to do with surface?’ This question from Bignia Corradini hangs in space. Yes, I think so, too. Whether she draws now and then, I ask her. ‘No, colour is not a line for me. Line is “drawing”. And I don’t draw. I put together or position—with diverse impossibilities and detours—various pictorial elements.’

Mid-June. It’s hot ... the blue of the sea can be seen as a nearly closed eld. Only a few darker furrows permeate the surface of the water. I descend a steep path to the rocky coast. The blue now has round whitecaps in some places. And a dark brown is mixed between them ... the cliffs of the coast. Swimming is unthinkable here. I walk along the coast on a small wooden walkway, until a section of beach with rows of lounge chairs appears. On the edge of the wooden walkway, I find a couple of rock formations and a few metres of sandy beach. I get undressed here and wade into the water. The waves are long and ow calmly towards me. With no white crests. My body is rocked gently back and forth. I swim two crests of waves further out and then try to stand in the waves once again. I look down. Under my feet is bright sand, green water, but also long black leaves of seaweed. They made the water black. Here, I no longer dare put my feet down. I look into the water for a long time.

I have a microscope on my desk with which I frequently look at small items, the dust of paint, grains of pigments, fingernails, hair. I can adjust the lens in such a way that I can always look deeper into other layers. I turn forward and back. When one looks into an abstract pattern, one is often reminded of what constructed and painted abstraction is also searching for.

I arrive at the boundaries of language again and again. I am increasingly at a loss for words to describe these pictures. I only still write happily in exclamation marks, commas, and semicolons ... and a sort of rare conjunctive. I gladly speak only of the fact that I stand in front of a picture in Bignia Corradini’s studio and sink into it again and again, look into the depths, under the light-green spot, under the band of red. I know that Bignia Corradini is now hiking in the mountains. And I would really like to be sitting and talking and laughing in her studio again. I write Bignia an imaginary message: I hope you are well and your hiking trip in the mountains is bringing you joy. I am in the process of writing for you, and I now and then see the abstractions that are in our world and have again and again occupied painting: the colours, the energy, the power, the light, the wind, the atmospheres ... and the deserted expanses. Usu. Aoin. Galu. The art of seeing microscopic detail with all its contrasts.

This defines the action in the painting of Bignia Corradini. It is a being-in-transit with her colours, with her brush, her hands, and the movements of her entire body. These movements lead into the depths. Bignia Corradini’s pictures lead one to perceive the depths, the interior, the seeing within the material of painting.

And Bignia Corradini never forgets the lightness of a bright, flying band, which is ultimately positioned above everything else.

1 Figs. Tacet, AOIN, Lichtung, Durchzug, Transfer

2 Theo von Doesburg, ‘Comments on the basis of concrete painting’,in Joost Baljeu (ed.), Theo van Doesburg (London: Cassell and Collier, 1974), pp. 181–82, esp. p. 182.

3 Ettore Sottsass Jr., ‘was dem einen der Raum ...’, in Margrit Weinberg Staber (ed.), Konkrete Kunst: Manifeste und Künstlertexte, Studienbuch 1 der Stiftung für konkrete und konstruktive Kunst Zürich (Zurich: Stiftung für konkrete und konstruktive Kunst, 2001), p. 71.

4 Georges Didi-Hubermann, Phasmes: Essays (Cologne: DuMont, 2001).

August 2018

© Sibylle Omlin, Aven

in: „Bignia Corradini: Painting | Painting 2000 – 2018 “,

Herausgeber: KERBER VERLAG, gebundene Ausgabe: 232 Seiten, 2018, 174 Farbabbildungen.

SIBYLLE OMLIN

Born 1965 in Zug (CH). Sibylle Omlin is an art historian, independent author, and curator and lives between Aven and Zurich. She studied German literature , art history, and modern history at the University of Zurich. From 1996 to 2001, she served as editorial assistant and art critic for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Since 1999, she has worked as a lecturer and mediator of art theory (including at the Zurich University of the Arts [ZHdK], the University of Zurich, and the University of Konstanz). From 2001 to 2009, she was professor at the Institute of Art at the HGK Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz in Basel (institute management). From 2009 to 2017, she was director of the ECAV Sierre (Ecole cantonale d’art du Valais). Omlin is the author and editor of numerous books and catalogue texts on painting, art in public space and landscape, electronic art and performance.

»Tacet«, 2002, Acryl auf Leinwand, 130x 180cm

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Lepkowski Studios Berlin

»AOIN« im Spiegelkasten, Acryl auf Leinwand, Holz, vier Spiegel, 97 x 97 cm

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Lepkowski Studios Berlin

»AOIN«, Blick in den Spiegelkasten, Ausschnitt, 2012

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Lepkowski Studios Berlin

»Durchzug«, 2015, Acryl auf Leinwand, 170 x 150 cm

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

»Lichtung«, 2017, Acryl auf Leinwand, 100 x 100 cm

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Lepkowski Studios Berlin

»Transfer«, 2015, Acryl auf Leinwand, 170 x 150 cm

© Bignia Corradini und VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2022 / Foto: Lepkowski Studios Berlin